2025 Multiparty Democratic General Elections: Turning a New Page for Myanmar?

MYANMAR NARRATIVE

The upcoming elections on 28 December 2025 will turn a new page for Myanmar, shifting the narrative from a conflict-affected, crisis-laden country to a new chapter of hope for building peace and reconstructing the economy. Myanmar is no stranger to “founding” elections. These founding elections, often held amidst challenging environments and imperfect processes, have historically produced defining moments of opportunity to tackle the country’s ongoing conflicts and allow it to take its rightful place in the international community to fulfil its obligations.

The first founding election in Myanmar in 1951 was full of challenges. After gaining independence in 1948, the country became engulfed in multi-coloured insurgencies. The post-independence government of U Nu was dubbed the “Yangon Government” due to its last line of defence being the former capital, Yangon. However, the Yangon government was able to launch counter-offensives in 1950, regaining control over Myanmar’s major urban centres, and decided to hold the promised elections in 1951. The election was held in three phases over a period of fourteen months – from phase one in June 1951 to phase three in April 1952. Many frontier areas – today’s ethnic states – could not hold elections, and 11 per cent of central Myanmar’s regions also missed voting because they remained under insurgent control. Amidst the threat of violence from insurgents and general instability across the country, the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League, led by U Nu, won a massive victory, and Myanmar enjoyed a decade of peaceful and prosperous democratic rule.

The second founding election occurred in 2010, when the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) convened the polls after successfully adopting the 2008 Constitution. These elections were organized after twenty years of Tatmadaw rule and just two years after the deadly Cyclone Nargis. A few political parties boycotted the process, and elections were not held at all in the entire Wa Self-Administered Division. Nevertheless, the elections successfully ushered in the government led by President U Thein Sein in 2011, which introduced comprehensive political liberalization and economic reforms across the country. From 2011 onward, for another decade, Myanmar was able to re-engage with the global community and achieve a “Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement” with eight ethnic armed organizations.

The environment for holding the upcoming elections this year is no less challenging. Several international organizations have pointed out that the majority of the country’s remote regions are experiencing severe armed conflicts. However, the State Security and Peace Commission is resolved to hold elections in 265 townships, covering 80 per cent of the total 330 townships in the country. Given the preceding conflicts, the Union Election Commission (UEC) has tried its best to conduct the elections in three phases – 102 townships on 28 December 2025, 100 townships on 11 January 2026, and 63 townships on 25 January 2026 – aiming to complete all three phases within a month. Given the active pledge of violent suppression of voting by non-state armed groups, the UEC has done its utmost to ensure maximum election coverage.

Election coverage has declined dramatically over the last three elections since 2010. The election was wholly cancelled in 5 townships in 2010 and seven townships in 2015, but suddenly increased to 15 townships in 2020. In 2020, elections were cancelled in nine out of 17 total townships in Rakhine State, although the conflict in northern Rakhine was less violent and concentrated in only a few villages at that time. Rakhine political parties called foul, arguing that the southern part of Rakhine State – where the ruling party was able to grab support from local populations against regional parties – was favoured. This time, however, the cancellations are due mainly to security reasons, not political manipulation.

Contrary to the views of ill-informed external observers who note election coverage as low as 50 per cent of the population, the recent 2024 national census suggests that the population living in the 65 election-cancelled townships constitutes only 13 per cent of the total population. Although these 65 townships represent 20 per cent of the total townships, they are located in remote areas where population density is much lower than in central Myanmar. In addition, the affected population may be even lower than the census estimates, since most of these conflict-affected populations may have already relocated to different parts of the country or neighbouring countries. Despite these structural weaknesses, the upcoming elections feature a few redeeming qualities that can generate positive outcomes from this, albeit imperfect process.

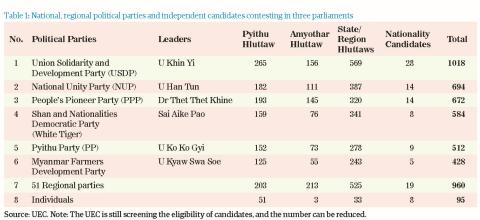

First, the participation of over 5,000 candidates from 57 political parties vying for an estimated 950 seats in three parliaments – the Pyithu Hluttaw (Lower House), Amyotha Hluttaw (Upper House), and State and Region Hluttaws – demonstrates a highly motivated group of citizens. These candidates paid costly candidacy registration fees of K500,000 to participate, knowing they are likely to lose the fees if they do not win. They have offered pledges to their constituencies ranging from lowering inflation to cleaning up garbage and draining sewage – thousands of worthy ideas for possible reform initiatives for the incoming government. The active cooperation from constituencies is also encouraging candidates to step up their last-minute, high-intensity door-to-door push in many areas, despite the UEC’s rules against certain types of canvassing due to security reasons.

Second, the introduction of the new Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) system to elect candidates for the Amyotha Hluttaw and State and Region Hluttaws has encouraged many ethnic political parties to enter the contest. The introduction of MMP into the Amyotha Hluttaw was a decisive incentive for ethnic parties, as half of the seats will be reserved for the compensation of seats to smaller parties. In the last three elections, the largest national parties – both the Union Solidarity and Development Party and the National League for Democracy – benefited from the British-style First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) electoral system used for all three types of parliaments. Smaller ethnic political parties representing Kayin, Kayah, Chin, and Pa-O groups never won a substantial number of seats, as large national parties defeated them in their home regions. Ethnic political parties such as the Shan and Rakhine narrowly won some seats due to the concentration of ethnic populations within their states; however, they were largely excluded from a substantial part of sub-national governments. The introduction of the MMP system will change the landscape in both the Amyotha Hluttaw and sub-national parliaments. Furthermore, the proposed change of Section 261 of the Constitution, as agreed by Tatmadaw, will allow certain ethnic political parties to choose their Chief Ministers or participate in sub-national government. This can be a major game-changer for ethnic states, where ethnic political parties can hope for better representation for the first time. Unlike previous FPTP systems that favoured large national parties, the MMP system will boost smaller ethnic and regional parties, allowing them to gain seats through the “compensatory mechanism” of proportional representation, as they consistently collected the second or third largest vote counts in previous elections.

Third, the combination of the MMP system and the creation of larger constituencies for proportional representation has provided breathing space for ethnic political parties facing the acute challenge of campaigning in their respective conflict-affected states. Although ethnic political parties, particularly in highly conflict-ridden regions such as Rakhine and Chin States, may see the majority of their Pyithu Hluttaw elections cancelled, they can still enhance their representation through the Amyotha Hluttaw. They can compensate with vote counts from the townships where elections are held through the MMP mechanism and larger constituencies. That is why five Rakhine political parties and three Chin political parties are contesting in the upcoming elections, even though they can barely match powerful national parties in terms of resources and protection. This gives an opportunity for non-armed ethnic leaders to gain popular support to organize effective mediation for conflict reduction and the negotiation of peace processes with various ethnic armed counterparts in their respective regions.

Fourth, for the first time in twenty years, women candidates have reached the highest percentage ever – 18 per cent of total registered candidates – surpassing the already high percentage of 15 per cent in the 2020 elections, when women office-holders were attracting more women into the political process. This is a welcome recognition of the role of women in peace, reconciliation, and nation-building, as many female candidates have raised hopes for the cessation of conflicts and the promotion of women’s and youth affairs. Public campaigns for higher voter turnout will benefit women and youth candidates. In fact, the use of the MMP system will also benefit smaller ethnic and regional political parties when voter turnout is higher.

Last but not least, the introduction of Myanmar Electronic Voting Machines (MEVMs) can not only address the unfinished issue of vote-counting irregularities but also step up electoral practices to a higher level of transparency and accountability through technological upgrades. The use of voting machines can erase the possibility of “invalid votes” caused by the handwritten procedures of the past. The ratio of wasted invalid votes was as high as five per cent in all three previous elections where paper ballots were used. Unlike what outside observers have wildly suggested regarding the possibility of electronic surveillance through the machines (claims which tend to exaggerate the capabilities of low-cost, locally-made MEVMs), public demonstrations on the use of MEVMs across the country have never raised doubts over the surveillance issue, as the machines do not have the sophisticated design required to capture additional information about voters.

To conclude, the Myanmar elections are being conducted in the interest of the Myanmar people and are being organized with the best humanly possible procedures and methods to maximize public participation despite the conflict and unstable environment. While the elections do not choose the elected government directly, they will choose candidates for the three parliaments, where the voice of the people can be reflected in future governance. With the new MMP electoral system, the election will also enhance the role of smaller ethnic and regional political parties in national affairs through compensatory mechanisms at the Amyotha Hluttaw. At the sub-national parliaments, these ethnic and regional political parties will surely gain representation this time, and they can immediately pick up the task of peace and reconciliation with their armed counterparts in different states and regions. Like previous founding elections in Myanmar, the upcoming elections have certainly brought hope and energy to people who have suffered for too long under ongoing conflicts. An election that strives for popular participation should be cherished, not condemned.